Francisco Carbajal, Unified Peaks, 2022

Scaffolding, woven plastic strapping, 11500 x 4200mm.

As the work creates a movement with the wind and the site, it reflects the dance of our consumed traces repeating in nature. Echoing the drift of micro-plastics carried in the elements a dance of dire consequence for ocean habitats and

Unified Peaks is a collaborative project designed to question the current environmental practices of both the architecture and construction industries. By fusing art and architecture, this work hopes to create a platform for discussion around circular economies for construction materials. It asks, “should the use of up-cycled materials become standard practice in the future?” and looks to ways that might be achieved.

Unified Peaks behaves as a shelter, expressing the fundamental purpose of architecture whilst simultaneously communicating the need to reframe that purpose for a contemporary social and ecological context.

Its form captures the calm yet potentially violent behaviour of the moana surrounding Waiheke Island. This contrast is mimicked in the sculpture’s design by the soft curves and aggressive points, all created using upcycled materials found at the fringe of construction: scaffolding poles are used as the outer frame and woven plastic strapping forms the screen for shading.

While enjoying shade from the sun, look for the QR codes hidden around the sculpture to learn more about this project.

Chris Moore, Introduced Species, 2022

Forged, fabricated steel, galvanised, copper paint. H2500-3600 x W1200-4000 x D80mm.

Lynn Margulis once wrote, “Life on earth is more like a verb.” As an evolutionary theorist and cellular-molecular biologist, she spent much of her own life observing the behavioural patterns of other lifeforms. She witnessed among them an unerring tendency toward greater diversity and symbiotic relationships with neighbouring beings, both big and small.

Human beings have been a force of great transformation within earth’s natural systems, though largely, this has been with a mind to homogenising environments to serve their immediate needs. Aotearoa’s natural landscape is one example of this, with species brought by settlers over the centuries having a dramatic effect on endemic and indigenous species, often resulting in decreased biodiversity.

Chris Moore’s grove of galvanised steel sculptures references this history of Introduced Species, and their enormous impact upon the land. But, in their transience, they also gesture to a way of living upon it with a lighter tread, exercising caution and care in our interactions so that they might be a force of reciprocity and regeneration like those of most other lifeforms.

Natalie Guy, The Genius Loci of the Chapel, #2, #3, #5, 2020

Fibreglass over polystyrene. H3000-3200 x W500-910 x D590-620mm.

Natalie Guy’s art practice engages mid-century Modernism from a contemporary perspective, attending to its slippages and failings just as much as its enduring appeal.

The Genius Loci of the Chapel (#5/#3/#2) are sculptural reinterpretations of Jim Allen and John Scott’s Futuna Chapel, Wellington (1961) and Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel, France (1955).

“‘Genius Loci’ refers to the distinctive atmosphere of a location, and in science fiction, it refers to a place with its own intelligence,” Guy explains. This characteristic is what her sculptures aim to capture: the tension of the buildings wherein they appear as expressions of a specific time, place, and vision, but also subtly unaligned with their surroundings, oriented to plural other times, places and visions.

Out of place in the natural landscape of Waiheke, Guy’s textured fibreglass columns are disruptive but transporting. Viewers might peer through one of the window-like cavities on their surface for a perspective on the familiar environment that is novel and unexpected, much like Guy’s perspective of Modernism and its legacy.

Margaret Feeney, Bird and Insect Bath, 2022

Hand built ceramic, with underglaze and glaze. 1000 x 520 x 480mm.

Bird and Insect Bath is a study of the garden birdbath that situates the familiar form within a larger conversation about water use, the built environment, and interspecies relationships as part of artist Margaret Feeney’s ongoing project, ‘Water Systems’.

Born from concern about Tāmaki Makaurau’s susceptibility to drought and its impact upon small creatures, the sculpture’s labyrinthine chambers and interconnected basins are designed to collect water and provide shelter for Waiheke’s birds and insects over the hot and dry summer months.

Much of Feeney’s work is conceived to counter the abstract, disembodied systems that mark the contemporary information economy. Using boisterous materials with visual and haptic presence, she looks to bridge the human and organic worlds, make “the case for kindness as the first principle of thought in human invention” and recognise the mauri of big and small entities.

Julie Moselen, Continuum Amplas, 2022

Corten Steel. 2500 x 2200 x 1950mm.

Julie Moselen undertook this work with the desire to make a ‘monumental’ sculpture for Te Whetumatarau Point that would be visible from the gulf as a bold celebration of nature’s rhythms and cycles.

At this scale, Moselen’s signature metalwork recalls the megalithic monuments found in her homelands of West Penwith of remote Cornwall. Alluding to the rituals and cosmologies of her pagan ancestors who fashioned them and embodying the deep reverence for the land that forms their heart-centre.

Like a sweeping, pirouetting Mobius strip in form, yet defying gravity in material, Continuum Amplas bridges the mathematical and the ethereal, the ordered and the intuitive, the human and the divine. The work intends to “explore and discuss that which is bigger than us yet within us”. Viewers are invited to commune with the work as a multi-sensory experience, activating the sculpture through their own touch and listening for how the wind, sunlight, and the surrounding expanse of the ocean also bring it to life.

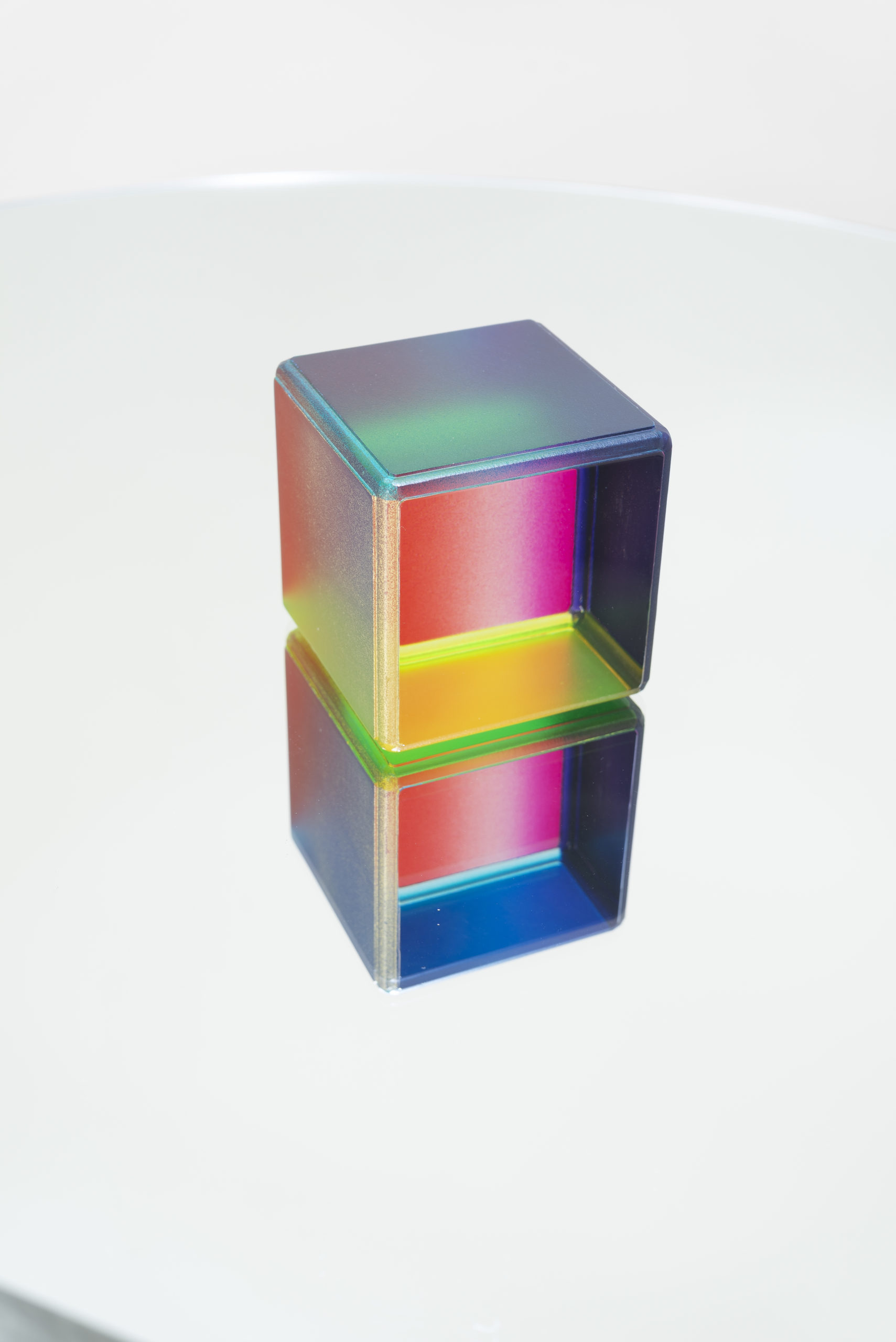

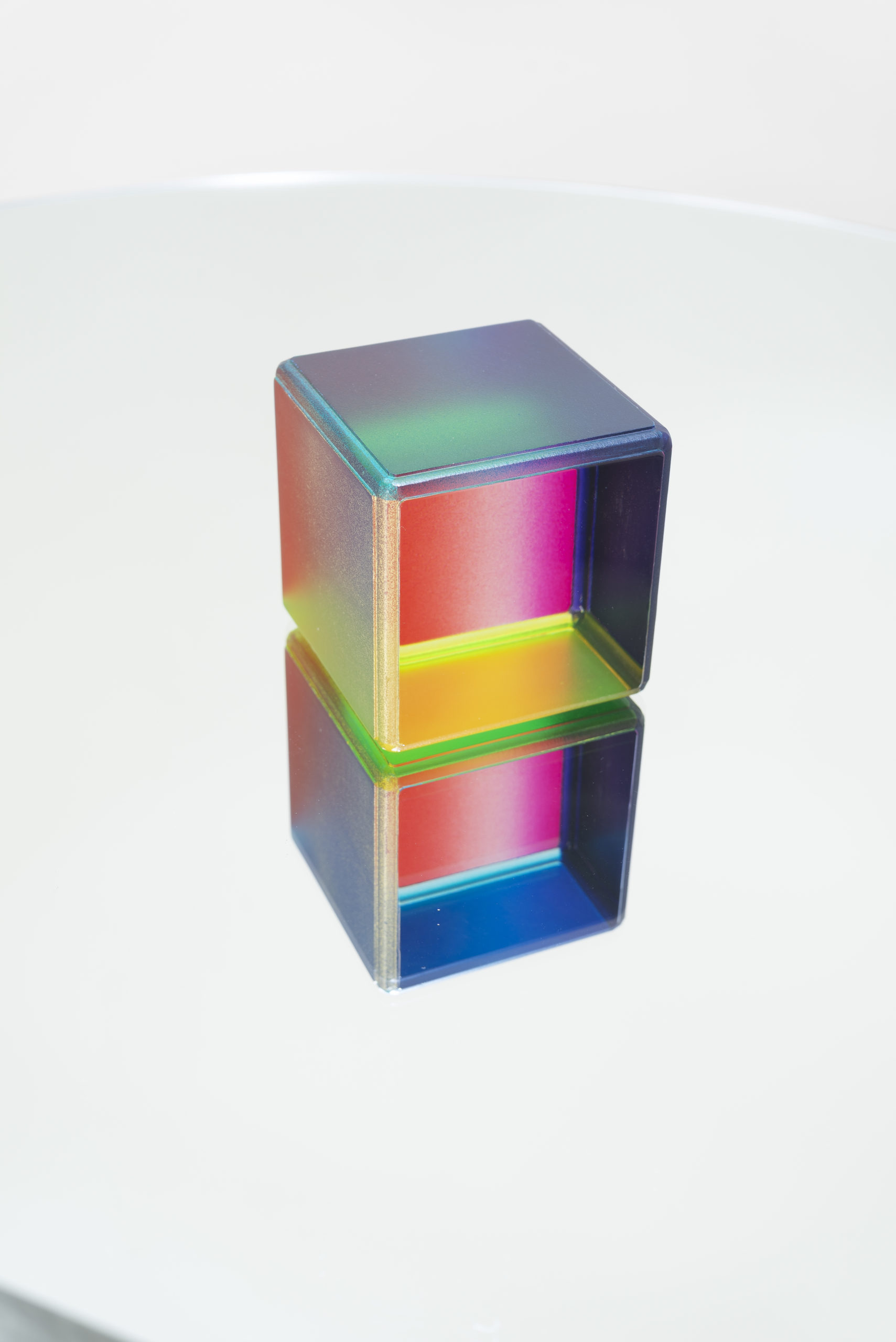

Johl Dwyer, Colour Tower, 2022

Resin, steel, oil and acrylic. 80 x 80 x 2200mm.

Johl Dwyer approaches colour as another artist might the ready-made. In colour, all elements of the artwork coalesce: concept, process, form, content, space, and affect become unified, while those boundaries that seem most fixed, as between liquid, solid and gas, or the object and its environment, seem to disintegrate.

His stacked cube sculptures are made by curing coloured pigments in resin, a material Dwyer describes as being “as close to ‘nothing’ or ‘air’ as possible” – unobtrusive, that is, but still rife with potential for unpredictable fluctuations and chance effects.

Colour Tower stands in counter to the grey, imposing cell towers that its tall form recalls, structures that disrupt the ecosystems they inhabit, both aesthetically and physically. Dwyer’s work, in contrast, seeks to be an expression of that ecosystem and a monument to its elemental power.

Using a palette of colours selected from the surrounding landscape, the sculpture might appear to have been formed spontaneously by the air itself – by a gulf-wind passing through and miraculously stilled in these cube forms, and with it, primordial motes of light, sea, sky and bush.

Ioane Ioane, Te Kura Nui from Nine heavens, 2022

Nikau palm sheaths, dry broad windmill palm, totara, harakeke, corten steel, plastic drainpipe tube, couplers 5000 x 3000mm.

The moa is a charismatic personality within Aotearoa’s natural history for many and Ioane Ioane is among those whose imagination it continues to capture. In Ioane’s case by the deep-time story of nature’s interconnectedness and transience that the ancient taonga embodies.

Using tōtara, harakeke and nikau palm sheaths, Ioane has fashioned a tactile sculptural interpretation of the moa, referring to its te reo Māori name, ‘Te Kura Nui,’ which translates as the many red feathers. These organic materials will disintegrate and shed slightly during installation, enacting the whakataukī: ‘All leaves return to their roots when they fall.’

Thinking of this whakataukī, Ioane reflects on how we remain connected to extinct creatures and beings like the moa and to lands we may no longer live in.

“As a Samoan,” he writes, “the moa symbolises for me not a loss but a celebration of the core softness of home and the thin veil separating Hawaiki and the living.”

Jorge Wright, Head Within, 2022

Corten Steel, 5000 x 3300 x 506mm.

Drawing inspiration from its surroundings, Head Within hopes to prompt a conversation on mental health in Aotearoa among visitors to the 2022 sculpture trail. A headland is made a headland by its exposure to the unforgiving elements of the ocean, against which the land must constantly form and reform itself to remain stable. Though as porous and volatile as any coastline, the threshold between the human mind and the outside world is not so visible and can be much harder to navigate.

On one level, the Russian-doll effect of Jorge Wright’s sculpture conveys the feelings of confusion and self-estrangement that often accompany mental health struggles. Nestled into one another but facing different directions, they conjure the sense of the mind turned against itself with doubt and insecurity. However, the openness of the figure encourages those struggling to ask for help: by being transparent and allowing others to enter our inner world, we can also let some light back in.

“I want to remind those going through dark times that there are brighter days ahead,” Wright says, “take a moment to reflect; there is beauty inside everyone; you just have to Head Within.”

Brit Bunkley & Andrea Gardner, Afternoon tea / Never odd or even, 2022

PLA, plastic, epoxy, acrylic paint and wooden furniture. Table dimensions 1700 x 1000 x 750mm.

Brit Bunkley and Andrea Gardner’s Afternoon tea / Never odd or even is a topsy-turvy-back-to-front take on our future in the Anthropocene.

Prodding at and riffing on everyday objects, their sculpture implies strange mutations taking place in creature and gravity alike at this eerie post-human tea party: things that don’t sink do; things that should end don’t; things that usually don’t have a seat at the table do.

These surreal visual puns plunge us into the (il)logic of human-induced climate change, which itself seems topsy-turvy and back-to-front. To the question of how we live with all these odd inversions, Bunkley and Gardiner’s work suggests that solidarity with the strange might be a good place to begin.

Lang Ea, KA BOOM!, 2016/2022

600+ red, acrylic pom poms, 3000m diameter.

Looking up into the overstory, visitors might easily mistake Lang Ea’s KA BOOM! for a late-blooming pōhutukawa. Like the tree’s flowers, the six hundred acrylic pom-poms comprising the work are of a vibrant red colour that stands out among the foliage. Yet KA BOOM! is blemish as opposed to a blossoming.

While the flowering of the pōhutukawa is cause for celebration, here the red signals a dark and complex history of global violence. By referencing comic book illustrations and language and using everyday craft materials, Ea invites a playful engagement with her work but ultimately forestalls it and urges viewers toward deeper reflection on what it is to live in the face and wake of war.

The work’s stillness, poised within the tree branches as if caught in a spider’s web, is refreshing as we see global powers rushing headlong into war at enormous psychological, spiritual, and cultural costs. Ea offers an artistic armistice; hushing the clamours of conflict, she creates a moment of fraught beauty that renders those costs so apparent and so essential to protect.